#75 A Perfect Storm: The Expected Black Swan of Carry Trade

Why Japan’s Market Collapse Was a Disaster Waiting to Happen (Not That We Foresaw It, Nor Tried To)

Welcome to the new era of Anker Capital Management! 🎉

If you’ve been following this newsletter for a while, you might have noticed a small change in the name. We’re no longer Edelweiss Capital; we’ve now rebranded as Anker Capital Management. Don’t worry, we haven’t been acquired by a giant conglomerate (yet!), but we have decided to step things up a notch and make this newsletter an even more powerful tool for sharing our ideas, thoughts, and reflections on investing.

While the name has changed, everything else remains the same... or better. Previously, I always tried to steer clear of day-to-day topics, but now, without those constraints, we’ll be able to talk about what truly excites and concerns us. And best of all, my colleagues will also have the opportunity to contribute their pieces. In short, this newsletter is becoming a platform where the entire Anker Capital team can share their insights and engage with our community.

Now, about today’s article…

This week, the financial world’s attention has been squarely on Japan, where the Nikkei index has experienced one of the most significant drops in its history. In just two days, the Japanese stock market lost all the gains it had accumulated over the past year, and the impact hasn’t been confined to Asia; it has also dragged down the markets in the United States and Europe. What triggered this collapse?

In the article, we dive into the details of this phenomenon, exploring how monetary policies, investor moves and economic concerns have combined to create this perfect storm in the markets.

Welcome to Anker Capital! If you are new here, join us to receive investment analyses, economic pills, and investing frameworks by subscribing below:

Madame Monet en costume japonais “La Japonaise” (1876). Claude Monet

1. The Bank of Japan’s Monetary Experiment

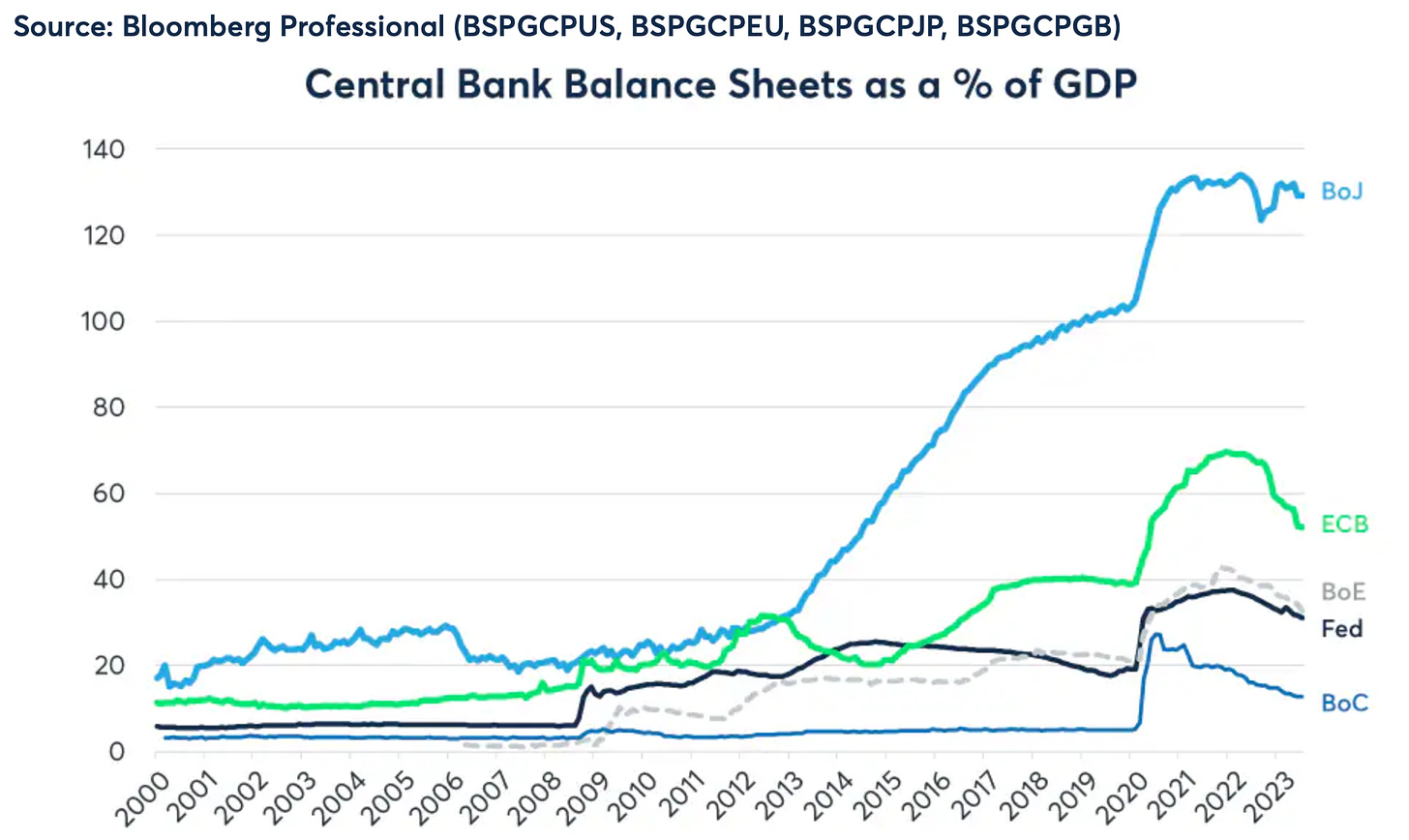

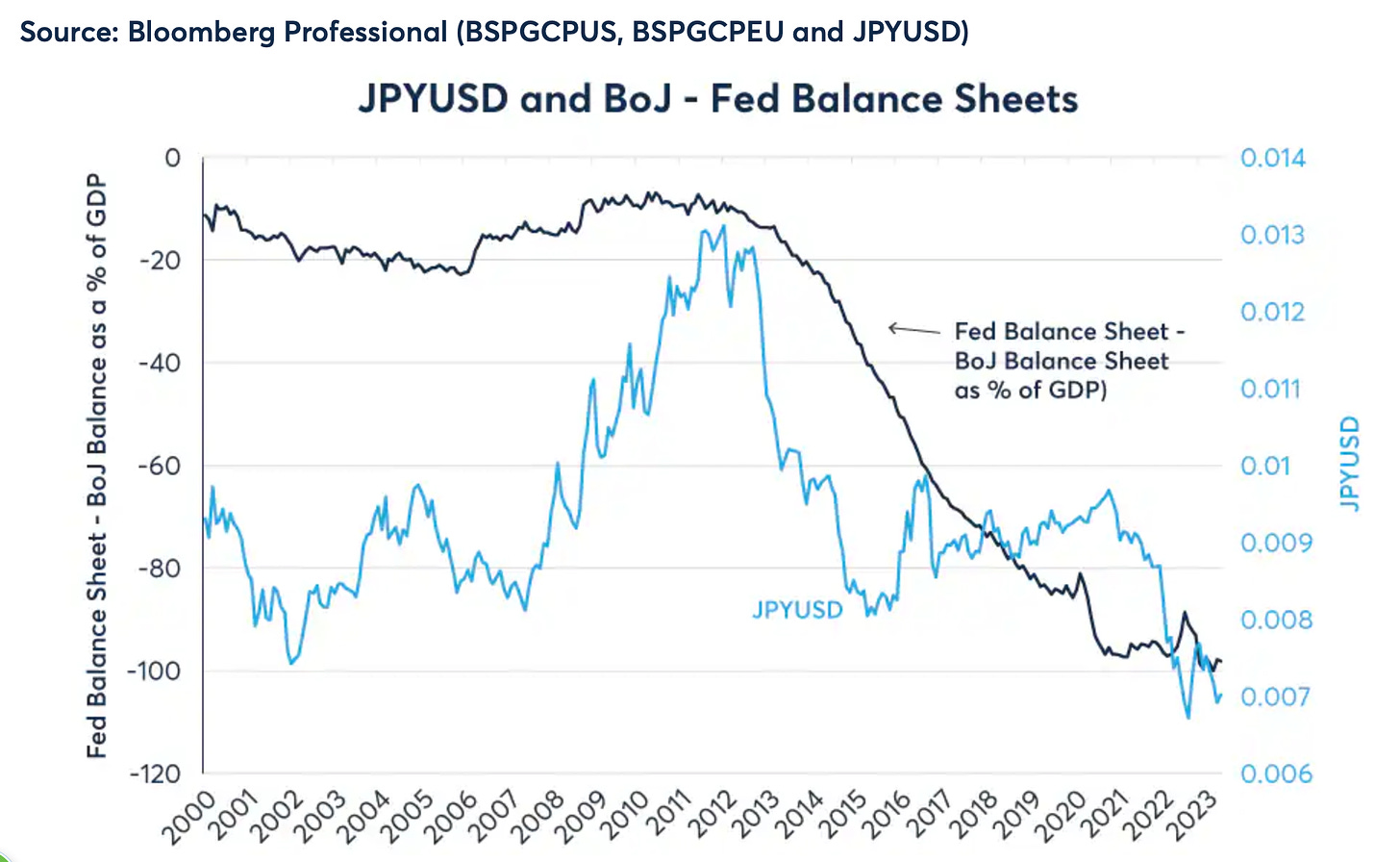

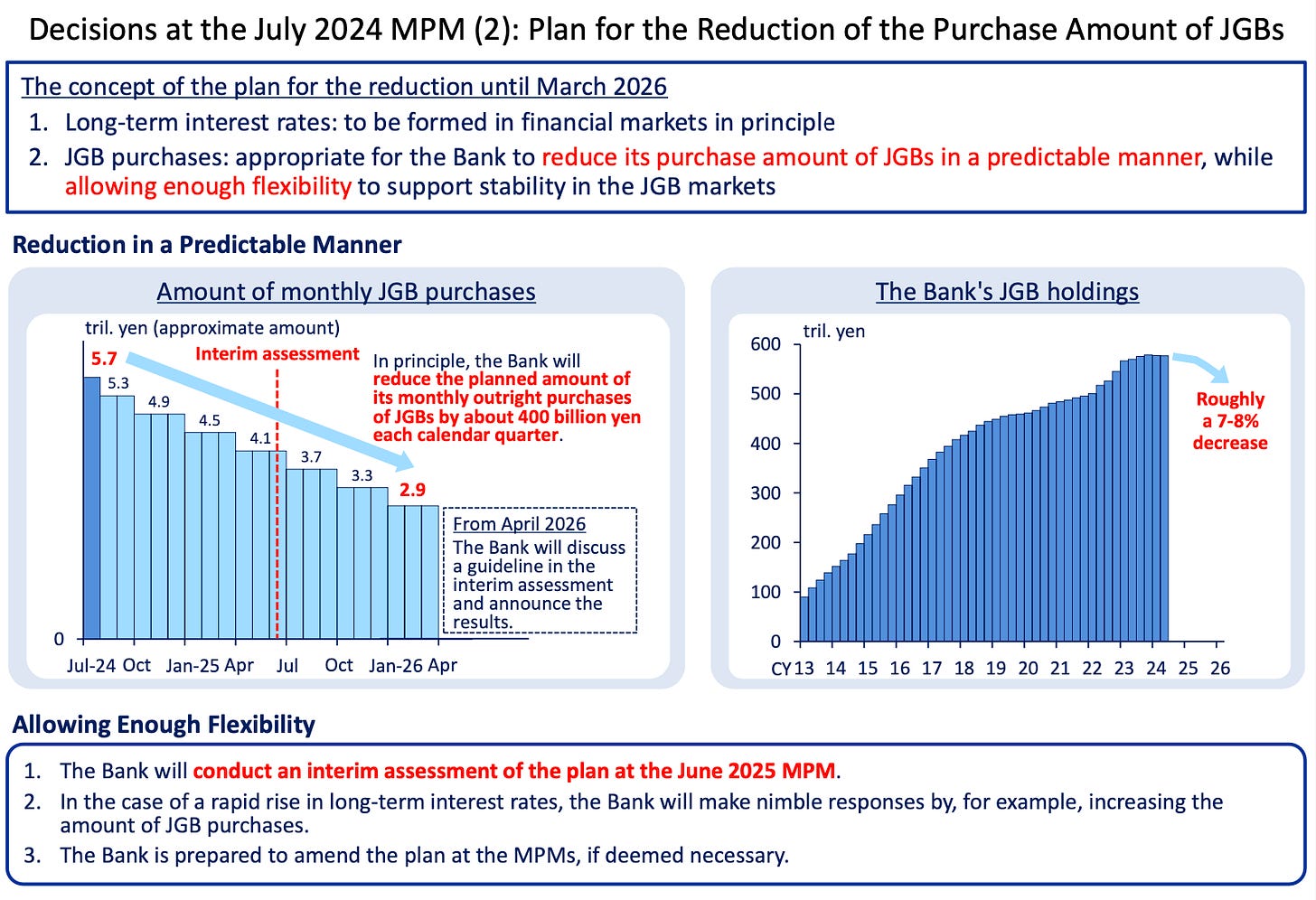

In recent years, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has implemented one of the most aggressive monetary policies globally, aiming to revive an economy that has been stagnant for decades. This approach has led to a massive expansion of its balance sheet, which has surged to 126% of Japan’s GDP.

This growth has been primarily driven by the need to finance a public debt that now exceeds 260% of GDP, a stark indicator of the country’s fiscal imbalances and the imperious need to fight demography and incentivise investments for growth.

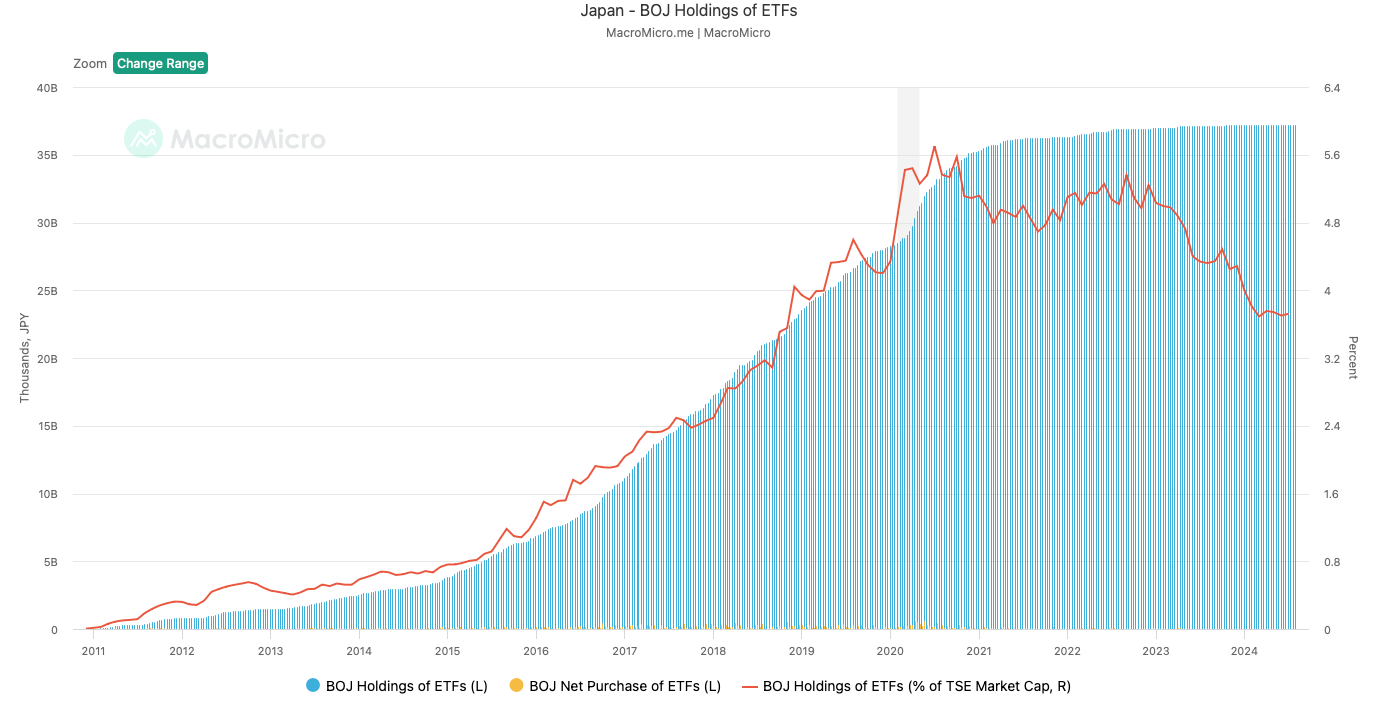

A key element of this strategy has been the large-scale purchase of financial assets, including ETFs that track the Nikkei index. The BOJ has become the largest holder of Nikkei ETFs, with a stake totaling $320 billion.

2. Understanding Carry Trade: The Risk and the Reality

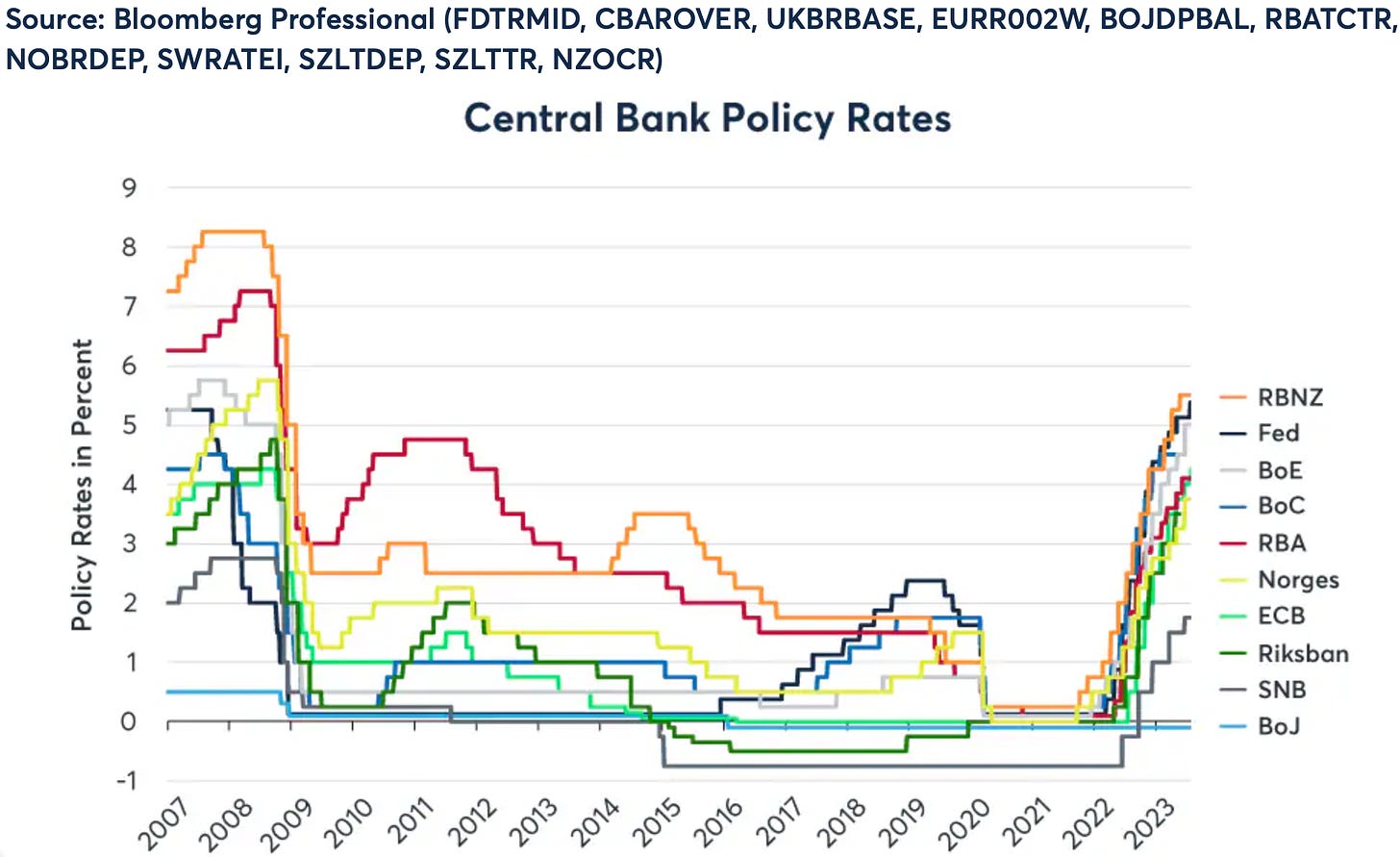

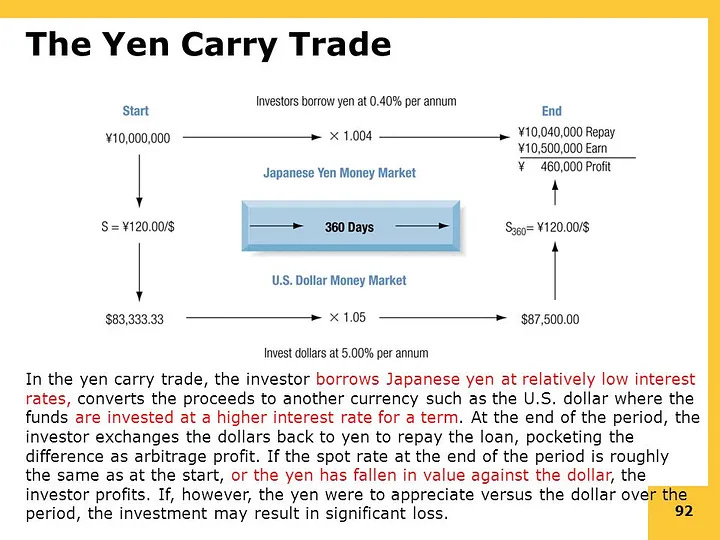

For the past 20 years, the Bank of Japan has maintained its interest rates near 0%, resulting in an exceptionally low cost of borrowing in yen. This environment has created an opportunity for financial arbitrage that can be quite profitable: borrowing in yen at virtually zero interest, converting those yen into euros or U.S. dollars, and using those funds to purchase financial assets that offer a higher return. For example, one might invest in U.S. government bonds or, for those willing to take on more risk, in equities of companies from these regions. This strategy, known as carry trade, becomes increasingly lucrative the larger the interest rate differential. Additionally, it becomes even more profitable if the yen depreciates. If the yen weakens against the dollar by the time the loan needs to be repaid, the yen can be repurchased at a much lower cost than when it was initially borrowed.

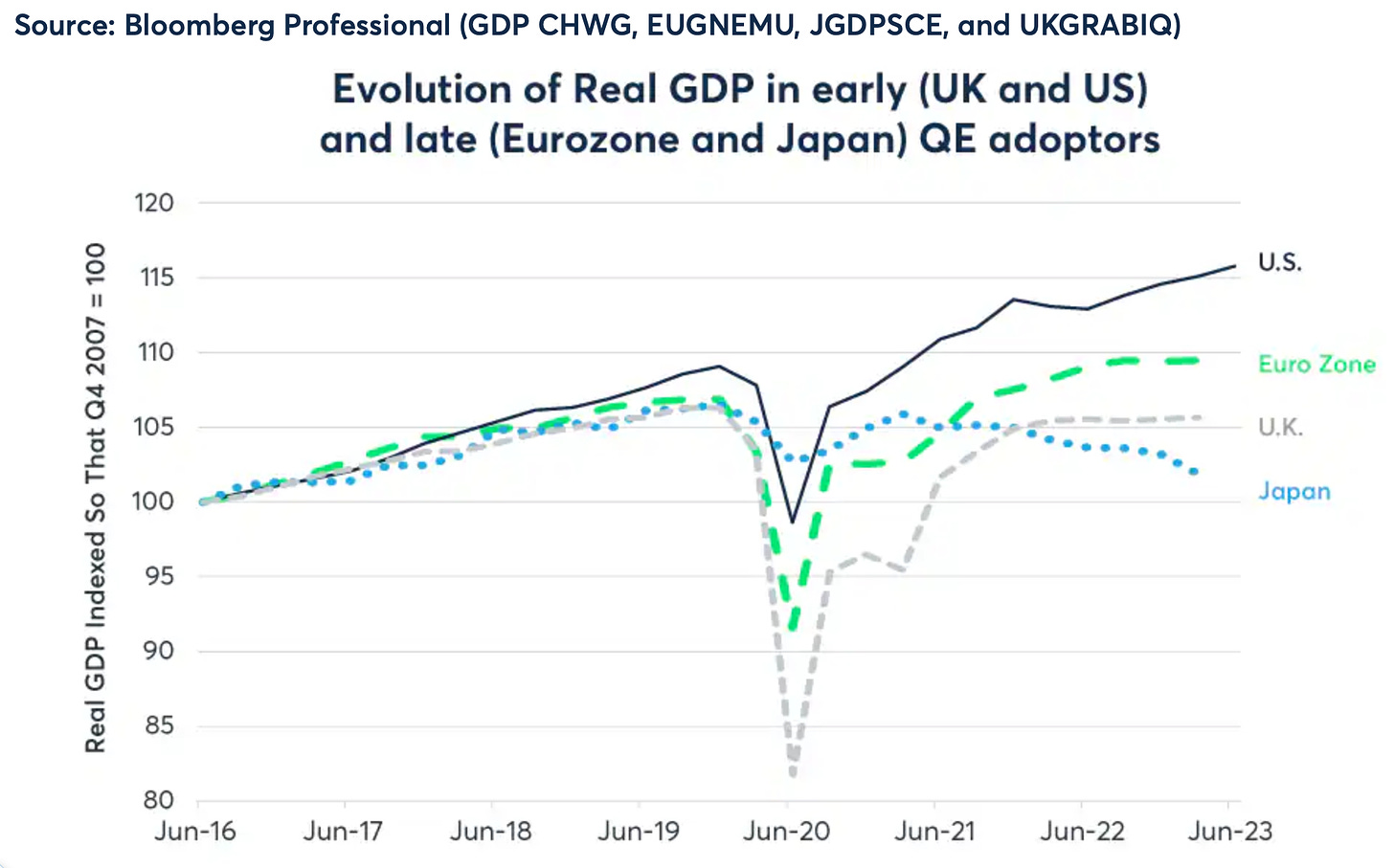

Now, let’s consider what has happened in global financial markets. Starting in 2021, the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and others have had to significantly raise interest rates to combat domestic inflation. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan chose not to raise its rates. This led to a widening interest rate differential between Japan and countries like the United States

As a result, starting in 2021, the carry trade became much more attractive than before. More investors, both inside and outside of Japan, began borrowing yen to invest abroad. Initially, this rush to short the yen and go long on dollars or euros led to a depreciation of the yen against these currencies. In fact, the yen-dollar exchange rate hit its lowest level since the 1980s just a month ago.

The more the yen depreciated, and the more it was expected to continue weakening, the more profitable the carry trade became. Investors were not only capturing the interest rate differential between Japan and the U.S. or Europe, but they were also reaping additional gains from the yen’s depreciation.

But really, who hasn’t thought of it before? Borrow money at a low rate, invest in something that yields more than your interest payments, and pocket the difference. It’s practically the financial version of a no-brainer. (Mortgages? Real estate investments? Buy a house, rent it out, and let it pay for itself?) In high finance, it sounds fancier calling it carry trade. It’s all sunshine and roses until, well, it’s not. And, as with all great things, the good times can’t last forever.

What happens when it all comes crashing down? Well, it’s kind of like playing a game of chicken, isn’t it? Everyone's racing towards the cliff, and it’s all fun and games until someone has to swerve. And let’s be honest, in this game, you really don’t want to be the last one to flinch. Because when the yen suddenly decides to stop playing along, when interest rates start shifting, that’s when the real fun begins. Suddenly, the whole brilliant strategy of borrowing cheap and earning high turns into a scramble to cover your bets before you lose your shirt. Ah, the thrill of the chase—until the inevitable cliff edge appears.

3. The Chain Reaction: Margin Calls and Market Collapse

And, of course, things started to go south…

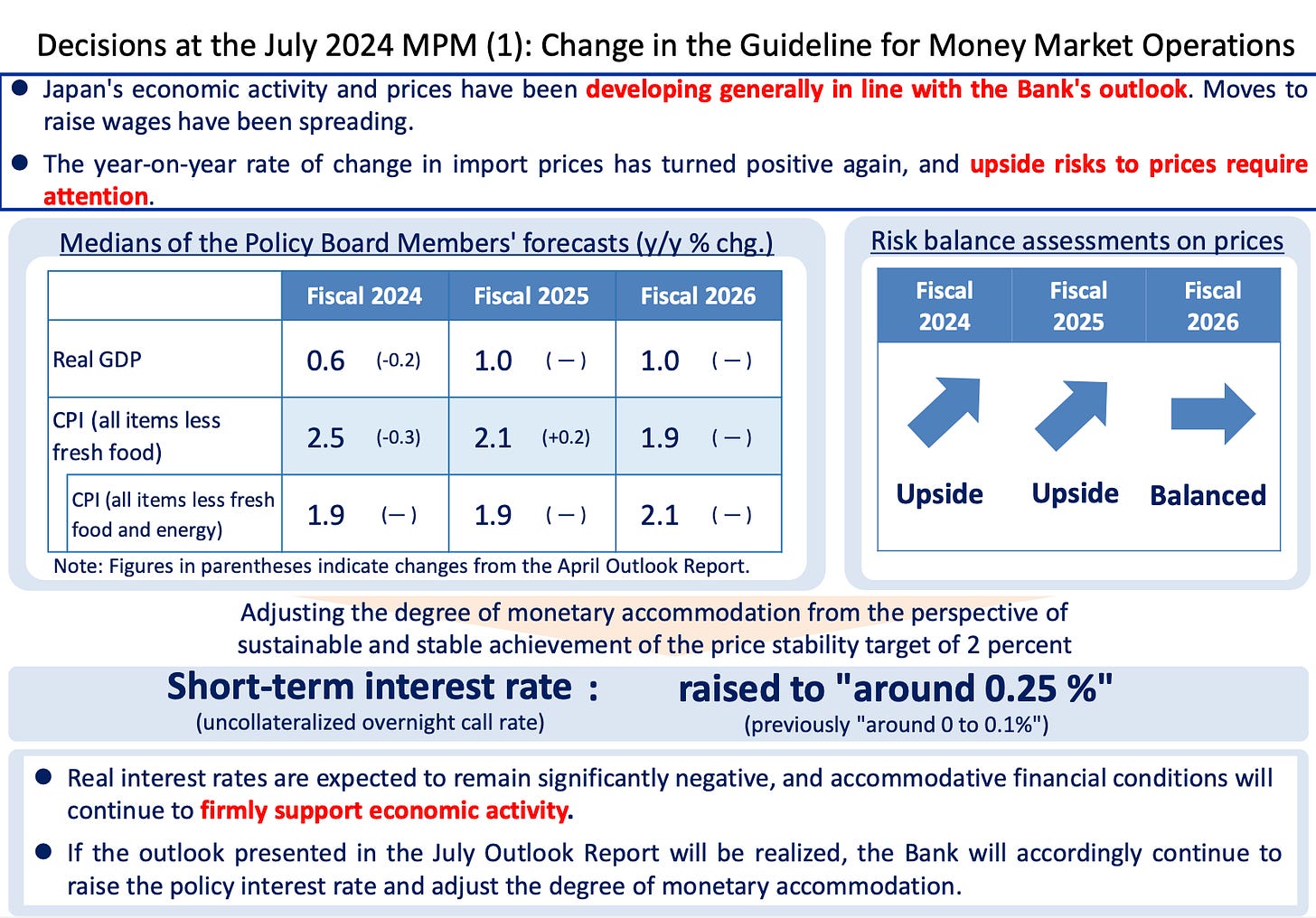

In recent days, the Bank of Japan made the announcement that it would be raising interest rates from 0% to 0.25%. And why this sudden move? Well, inflation seems to have taken root in Japan, stubbornly holding above 2% and even reaching 2.5%. (And, let’s not forget, they also wanted to shore up the yen’s value.) So, in an attempt to counteract the effects of their own policies, they decided to nudge interest rates up by 0.25%, hinting that further increases might follow (though they’ve already started backtracking on that).

Meanwhile, a stream of negative economic data, not just from Europe but particularly from the United States, has led many to believe that the Federal Reserve might start cutting interest rates as soon as September.

Now, if interest rates in Japan are expected to rise while rates in the Eurozone or the U.S. are likely to fall, the carry trade suddenly loses its appeal. Not only that, but as more and more investors steer clear of the carry trade, the forces that were driving the yen’s depreciation begin to weaken. The yen, instead of continuing to fall against the dollar or euro, starts to gain strength. Naturally, if the expectation shifts from a weakening yen to an appreciating one, the profitability of the carry trade, which was already diminished due to the narrowing interest rate differentials between the U.S., the Eurozone, and Japan, becomes even less attractive.

As a result, many investors who had open positions in this carry trade began to see their potential profits shrink and their risks rise. Their next move? Unwind the carry trade, which essentially means selling off some of their assets—whether those are denominated in euros, dollars, or yen—to pay down, cancel, or close their yen-denominated debt. And, of course, this liquidation of assets to reduce or eliminate debt puts downward pressure on the prices of those assets.

This is where the margin call comes into play. When an investor takes out a loan, it’s typically secured by some form of collateral, often in the form of financial assets. The lender might say, “I’ll loan you 100, but you need to provide collateral worth 200, because if I sell those assets in the market, I’m confident I can recoup the 100 I’ve loaned you.” However, the value of those financial assets fluctuates daily. If the value of the collateral you provided drops below 150% of the loan amount, the lender issues a margin call—a demand for additional collateral to back up the loan. If you’re unable to meet this margin call—meaning, if you can’t provide new assets to bring your total collateral up to at least 200% of the loaned amount—then the lender will sell off your collateralized assets to recover their money.

And this is precisely what has happened, primarily in the Japanese stock market, but also to a lesser extent in other global markets. We’ve seen a global margin call that those who borrowed in yen couldn’t meet. As a result, assets denominated in dollars, euros, and especially yen were forcibly liquidated, causing a significant sell-off. When these yen-backed assets are dumped en masse, regardless of the sale price, the inevitable outcome is a dramatic drop in Japan’s stock index.

4. The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Beyond Macro

We never focus much on macro movements, and we tend to avoid always talking about the macro economy, but trying to understand historic days like last Monday is important.

Beyond just market fluctuations, these events highlight the deep-seated vulnerabilities that persist in the global economy. The overreliance on loose monetary policies and central bank interventions has created an environment where financial markets can inflate artificially, only to crash when conditions change. This pattern is nothing new; we saw it during the 2008 financial crisis, and it has reappeared in Japan’s market collapse.

It’s essential to recognize that these historic days aren’t just anomalies or isolated events. They are warning signs that the global financial system is built on shaky foundations, where the balance can easily be disrupted by erratic monetary policies, leveraged by rampant speculation. These events also suggest that the risk of future crises is always present, particularly if the key players in the global economy continue to rely on the same strategies that have proven unsustainable in the long run.

If you enjoyed this piece, please give it a like and share!

Anker Capital is a regulated investment firm (www.anker-capital.com)

We currently offer segregated accounts for qualified professional investors. If you are interested, feel free to contact us at investors@anker.ag

Disclosure: This post and any attachments are for general informational purposes only regarding our activities and do not constitute investment advice, or an investment recommendation for any investment product.

The author or Anker Capital Management may own the securities discussed. Please read our Legal & Regulatory Disclosures for further details.

Thanks! Yours is the first piece that helped me understand why the Japanese stock market crashed with the unwinding of the carry trade. Global markets fell because those who had the carry trade were closing their carry trade (having used Yen loans to fund global asset purchases)... but if I got this finally - the Nikkei fell because the Japanese institutions that had funded the carry trade must have got the Nikkei index (or stocks) as collateral and were selling it to reduce their exposure to the carry trade as the lenders to the investors who were investing in the carry trade. Is that fair?

Thank you! Have a great weekend!